News

Coastal Defenders: Protecting the Nation’s Coasts with Natural Solutions

Forty percent of the nation’s population, $9 trillion in contributions to the U.S. economy every year and 1,700 Department of Defense-managed military installations — that’s what is vested on the 95,471 miles of United States shoreline. Experts predict that within the next 30 years, the sea level along the U.S. coastline will rise an average of 10-12 inches and cause a profound shift in coastal flooding. At risk is much of the infrastructure, communities, resources and ecosystems on which our nation relies.

Recognizing the need to safeguard America’s coastlines and the value natural structures play in their protection, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, are finding ways to use materials science to support coral reef growth and restoration.

“Coral and oyster reefs, mangroves and seagrasses are all essential to attenuate large waves and storm surge,” explained Marisa Hughes, assistant program manager for the Biological and Chemical Sciences Program in APL’s Research and Exploratory Development Department (REDD). “These structures slow waves down and hold on to the ground to reduce erosion. As we adjust to live in a world impacted by climate change, we need to think about innovative ways to handle this additional threat.”

A Call to Action

Hughes is the founder and co-leader of the APL Climate Network, a Laboratory-wide initiative addressing the national and global challenges resulting from climate change. Part of that role involves incubating new research in understanding, mitigating and adapting to the rapidly changing environment. When Hughes launched a small internal challenge several years ago, Jenny Boothby, a biomaterials engineer in REDD’s Multifunctional Materials and Nanostructures Group, began to brainstorm.

“I have a background in biomedical engineering and remembered reading a paper about using coral skeletons as bone tissue implants,” Boothby recalled. “I just sat with that idea for a minute and thought, ‘What if we reverse that process?’ It’s common practice to build ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue; maybe we could do that for corals too.”

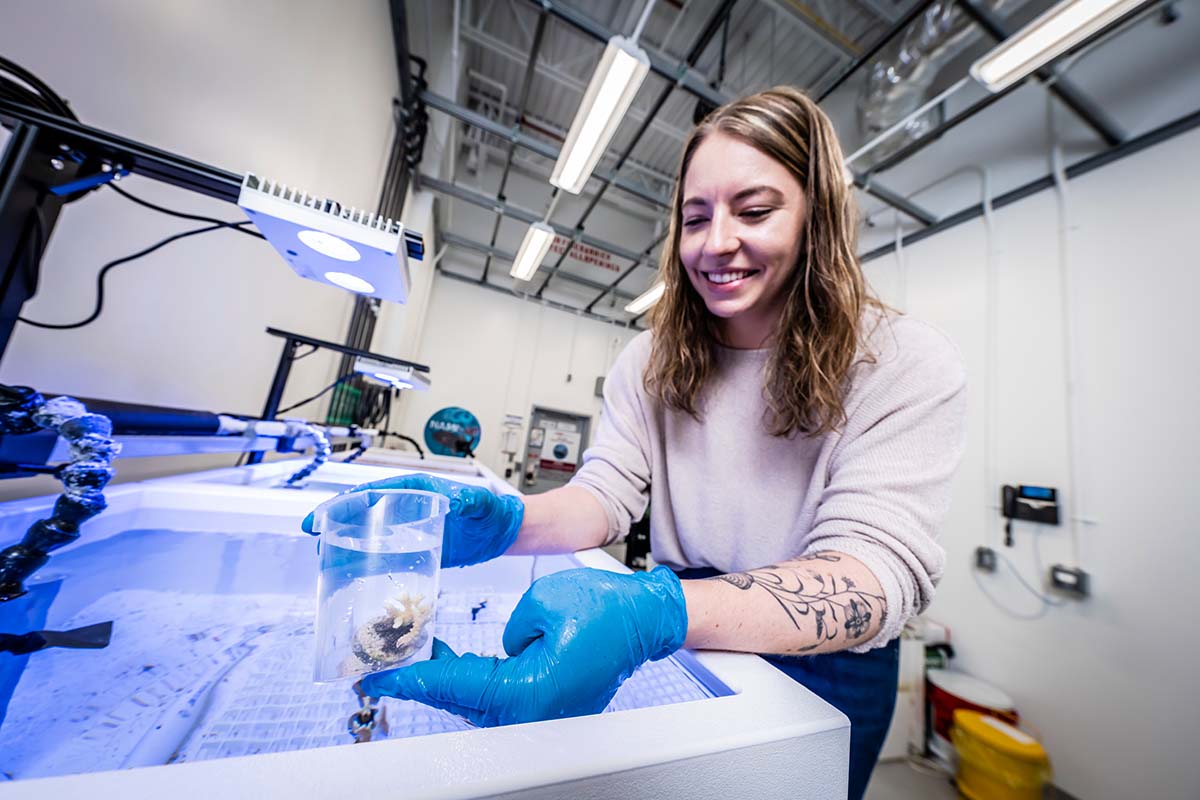

Boothby teamed up with the Lab’s marine science researchers, including Maddison Harman, a marine biologist, on internally funded projects to explore coral scaffolds. The group utilized tools and technologies within APL’s NAMI facility, a 3,000-square-foot, first-of-its-kind laboratory dedicated to unique maritime biology research, that houses aquariums sized from 10 to 1,000 gallons and the capability to make its own seawater.