Press Release

NASA’s Hubble Telescope Finds Potential Kuiper Belt Targets for New Horizons Pluto Mission

Artist’s impression of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft encountering an object in the distant Kuiper Belt, the vast disk of icy debris left over from our Sun’s formation 4.6 billion years ago. Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) are a unique class of solar-system body that has never been visited by interplanetary spacecraft. They contain well-preserved clues to the origin of our solar system. NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has uncovered three KBOs that New Horizons could potentially visit after it flies by Pluto, its primary mission target, in July 2015. The KBOs were detected through a dedicated Hubble observing program by a New Horizons search team that was awarded telescope time for this purpose.

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

Peering out to the dim, outer reaches of our solar system, NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has uncovered three Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) the agency’s New Horizons spacecraft could potentially visit after it flies by Pluto in July 2015.

The KBOs were detected through a dedicated Hubble observing program by a New Horizons search team that was awarded telescope time for this purpose.

“This has been a very challenging search and it’s great that in the end Hubble could accomplish a detection — one NASA mission helping another,” said Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, principal investigator of the New Horizons mission.

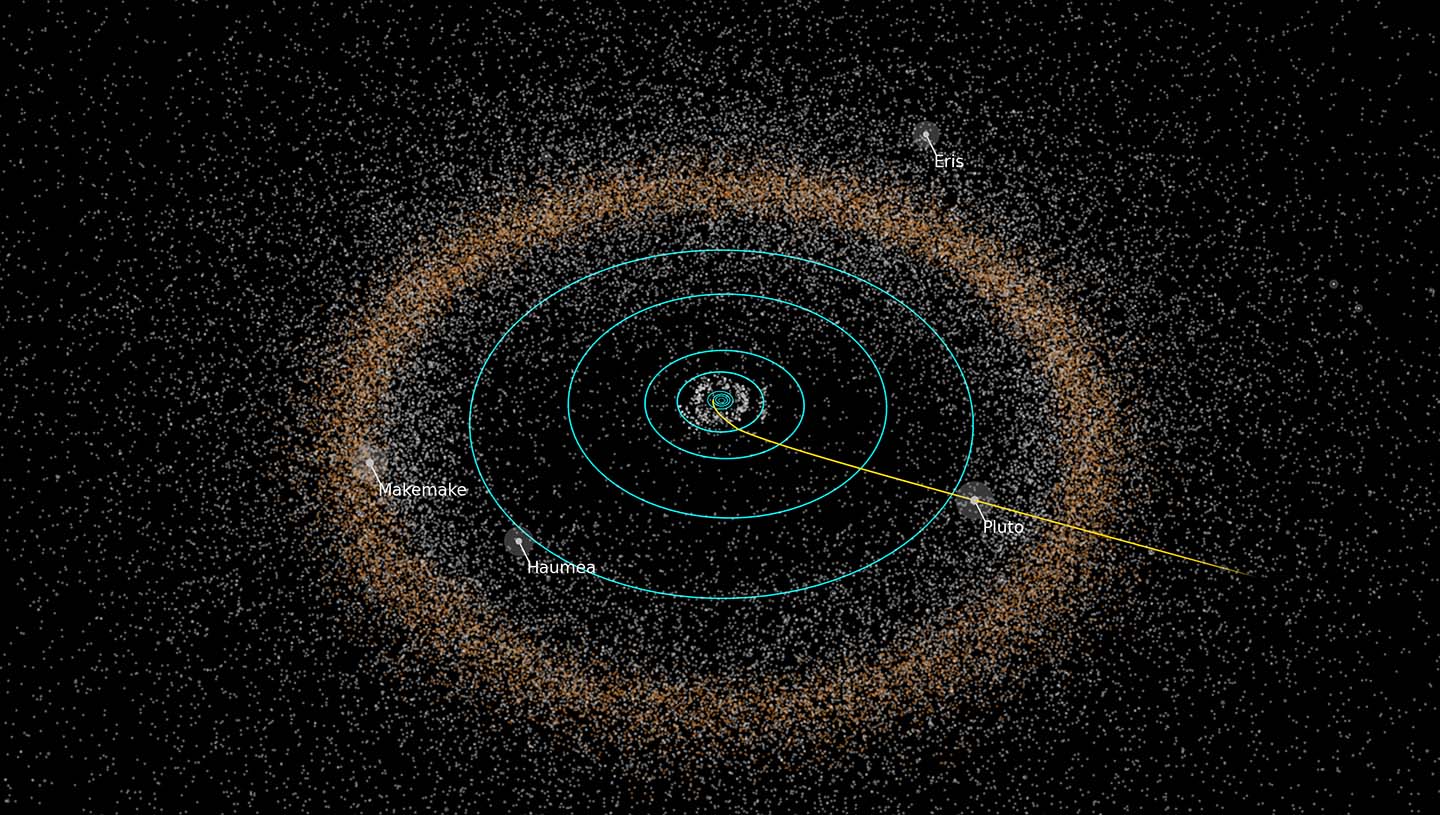

This perspective view shows the path of NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft (yellow) through the outer solar system and the Kuiper Belt. The orbits of the terrestrial and giant planets are shown in blue. The dots show the locations of representative asteroids, close to the sun, and Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs), which are mostly beyond the orbit of Neptune, the outermost giant planet.

Members of the “cold classical” Kuiper Belt, the most pristine part of the belt, which New Horizons will pass through after its Pluto encounter, are shown in orange. The largest KBOs are labeled — although note that Eris, Makemake and Haumea are situated farther from the cold classical belt than is apparent from the perspective of this diagram. Most of the fainter KBOs shown are not real objects, but represent the expected numbers and positions of all KBOs larger than about 100 kilometers (60 miles) in diameter, extrapolated from existing surveys.

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute/Alex Parker

The Kuiper Belt is a vast rim of primordial debris encircling our solar system. KBOs belong to a unique class of solar system objects that has never been visited by spacecraft and which contain clues to the origin of our solar system.

The KBOs Hubble found are each about 10 times larger than typical comets, but only about 1-2 percent of the size of Pluto. Unlike asteroids, KBOs have not been heated by the sun and are thought to represent a pristine, well-preserved deep-freeze sample of what the outer solar system was like following its birth 4.6 billion years ago. The KBOs found in the Hubble data are thought to be the building blocks of dwarf planets such as Pluto.

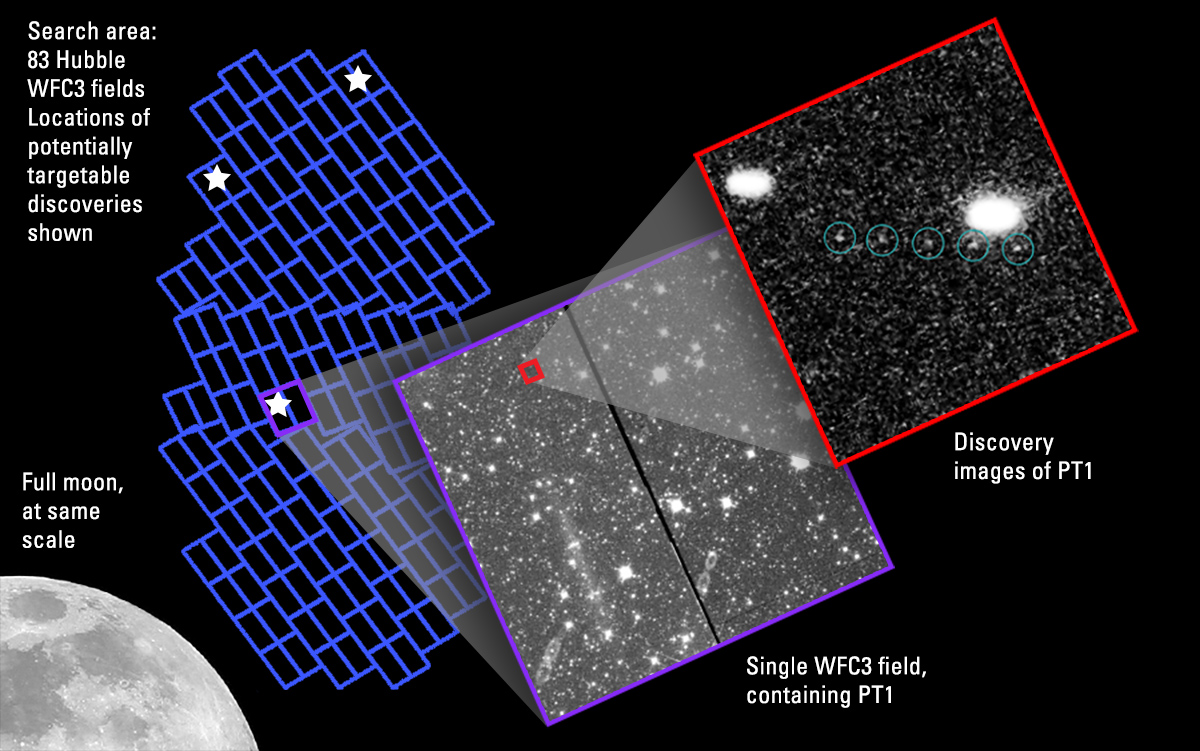

To find Kuiper Belt objects (KBOs) reachable by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, the Hubble Space Telescope took a total of 830 images of 83 pieces of sky (“fields”), covering an area similar to the size of the full moon. In this graphic, each pair of blue rectangles shows the size and position of a single Hubble field. The pair of rectangles represents the twin CCD detectors of the Hubble Wide-Field Camera 3 (WFC3) used for the survey. The white stars show the approximate positions where three KBOs that are potentially reachable by New Horizons were discovered. The purple outline shows the Hubble field containing object “PT1,” and the red outline shows the tiny fraction of that field in which PT1 was found. A combination of five images shows PT1 (circled) moving against the star background.

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

The New Horizons team started to look for suitable KBOs in 2011 using some of the largest ground-based telescopes on Earth. They found several dozen KBOs, but none was reachable within the fuel supply available aboard the New Horizons spacecraft.

“We started to get worried that we could not find anything suitable, even with Hubble, but in the end the space telescope came to the rescue,” said New Horizons science team member John Spencer of SwRI. “There was a huge sigh of relief when we found suitable KBOs; we are ‘over the moon’ about this detection.”

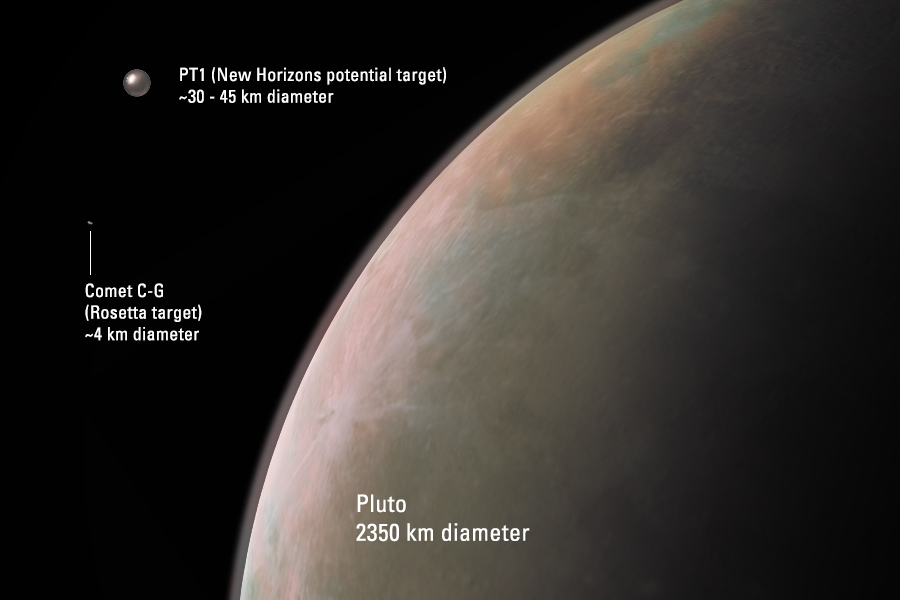

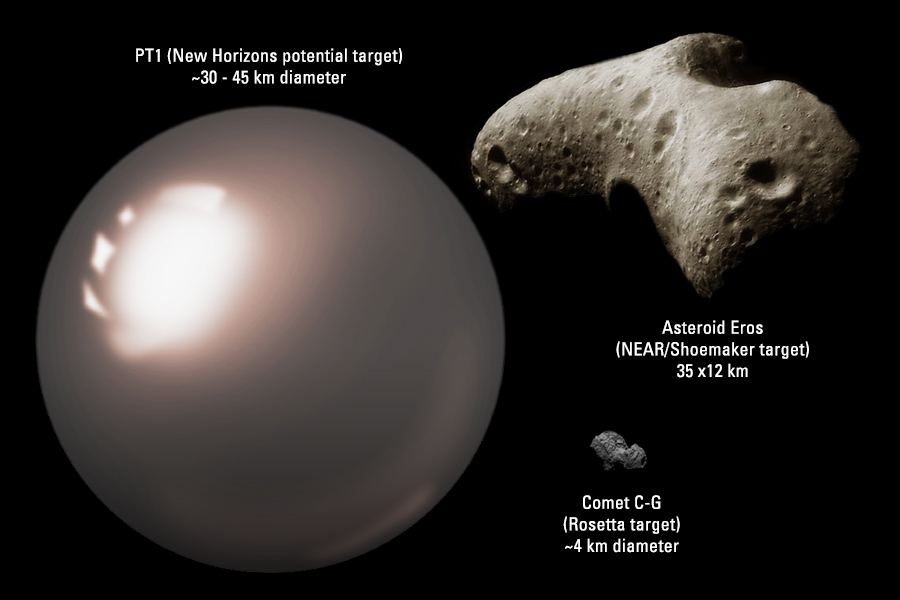

This composite image illustrates the size of “PT1,” a Kuiper Belt object (KBO) recently discovered with the Hubble Space Telescope and potential flyby target for NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, relative to New Horizons’ prime target, Pluto, and the target of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission, comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (“C-G”). PT1 is much bigger than typical comets like C-G, which may itself have originated in the Kuiper Belt, and may be a fragment of a parent body similar to PT1. However, it is much smaller than Pluto, the largest object in the Kuiper Belt, which may have formed from building blocks similar to PT1. Exploration of KBOs like PT1 might tell us much about the origin of both comets and larger objects like Pluto.

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

Following an initial proof of concept of the Hubble pilot observing program in June, the New Horizons Team was awarded telescope time by the Space Telescope Science Institute for a wider survey in July. When the search was completed in early September, the team identified one KBO that is considered “definitely reachable,” and two other potentially accessible KBOs that will require more tracking over several months to know whether they too are accessible by the New Horizons spacecraft.

This was a needle-in-haystack search for the New Horizons team because the elusive KBOs are extremely small, faint, and difficult to pick out against a myriad background of stars in the constellation Sagittarius, which is in the present direction of Pluto. The three KBOs identified each are a whopping 1 billion miles beyond Pluto. Two of the KBOs are estimated to be as large as 34 miles (55 kilometers) across, and the third is perhaps as small as 15 miles (25 kilometers).

This composite image illustrates the size of PT1, a potential New Horizons target Kuiper Belt object (KBO) discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope, relative to the target of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission target, comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (“C-G”), and the target of NASA’s NEAR/Shoemaker mission, near-Earth asteroid Eros. PT1 is much bigger than typical comets like C-G. However typical comets may be fragments of KBOs similar to PT1, and exploration of KBOs like PT1 may thus tell us much about the origin of comets. Scientists expect KBOs to be very different from similar-sized asteroids because the KBOs formed much farther from the Sun.

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

The New Horizons spacecraft, launched in 2006 from Florida, is the first mission in NASA’s New Frontiers Program. Once a NASA mission completes its prime mission, the agency conducts an extensive science and technical review to determine whether extended operations are warranted.

The New Horizons team expects to submit such a proposal to NASA in late 2016 for an extended mission to fly by one of the newly identified KBOs. Hurtling across the solar system, the New Horizons spacecraft would reach the distance of 4 billion miles from the sun at its farthest point roughly three to four years after its July 2015 Pluto encounter. Accomplishing such a KBO flyby would substantially increase the science return from the New Horizons mission as laid out by the 2003 Planetary Science Decadal Survey.

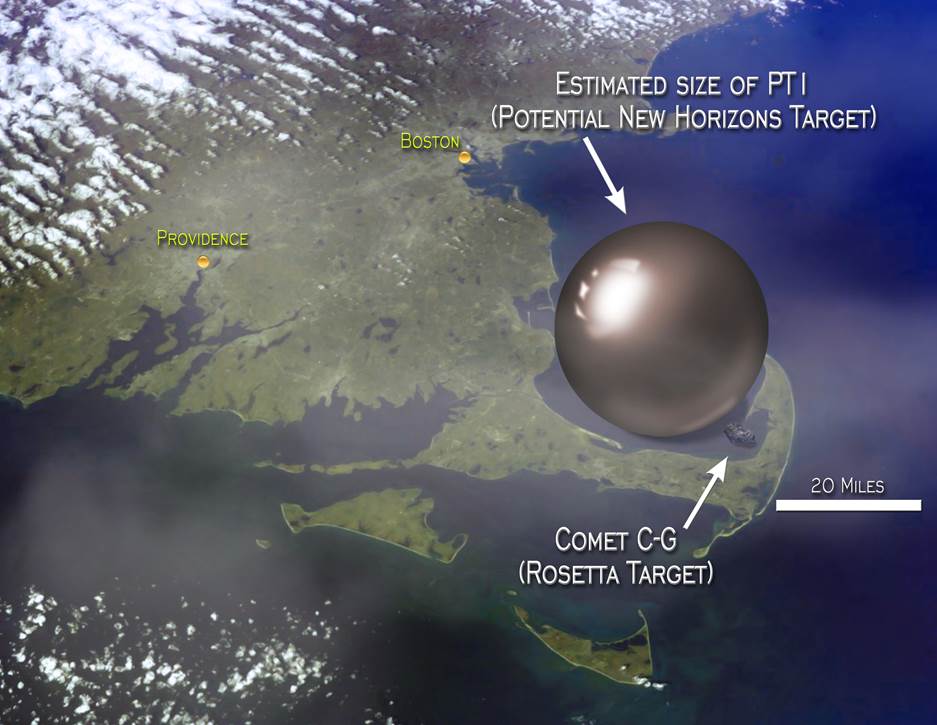

This composite image illustrates the size of PT1, a potential New Horizons target Kuiper Belt object (KBO) discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope, relative to the target of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission target, comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (“C-G”), relative to the Cape Cod region of New England. PT1 is much bigger than typical comets like C-G. However typical comets may be fragments of KBOs similar to PT1, and exploration of KBOs like PT1 may thus tell us much about the origin of comets.

Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, manages the New Horizons mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. APL also built and operates the New Horizons spacecraft.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and the European Space Agency. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., in Washington.

For images of the KBOs and more information about Hubble, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/hubble.

For information about the New Horizons mission, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/newhorizons and http://pluto.jhuapl.edu.

Areas of Impact

Media Contacts

The Applied Physics Laboratory, a not-for-profit division of The Johns Hopkins University, meets critical national challenges through the innovative application of science and technology. For more information, visit www.jhuapl.edu.