News

AI Reveals New Way to Strengthen Titanium Alloys and Speed Up Manufacturing

Producing high-performance titanium alloy parts — whether for spacecraft, submarines or medical devices — has long been a slow, resource-intensive process. Even with advanced metal 3D-printing techniques, finding the right manufacturing conditions has required extensive testing and fine-tuning.

What if these parts could be built more quickly, stronger and with near-perfect precision?

A team comprising experts from the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Maryland, and the Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering is leveraging artificial intelligence to make that a reality. They’ve identified processing techniques that improve both the speed of production and the strength of these advanced materials — an advance with implications from the deep sea to outer space.

“The nation faces an urgent need to accelerate manufacturing to meet the demands of current and future conflicts,” said Morgan Trexler, program manager for Science of Extreme and Multifunctional Materials in APL’s Research and Exploratory Development Mission Area. “At APL, we are advancing research in laser-based additive manufacturing to rapidly develop mission-ready materials, ensuring that production keeps pace with evolving operational challenges.”

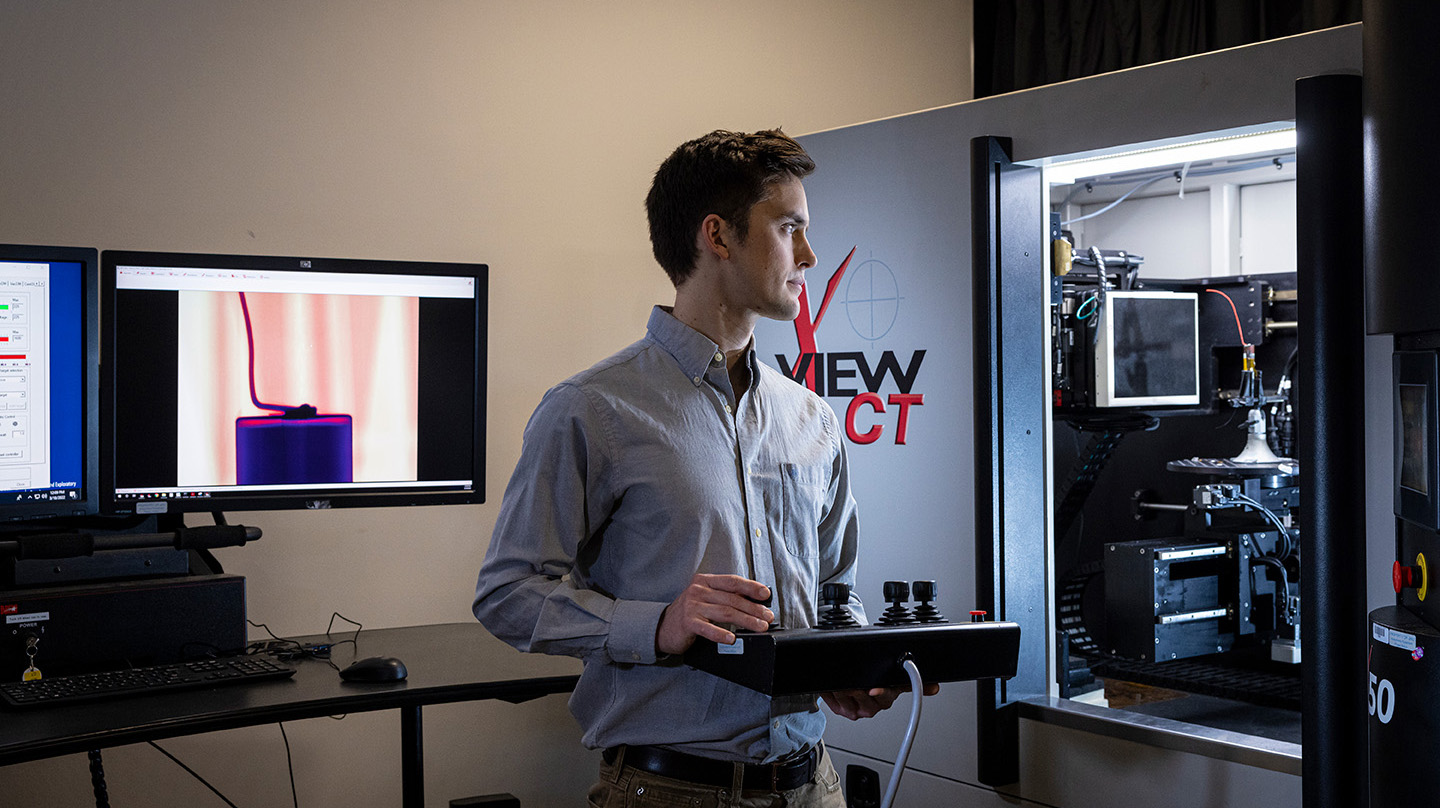

The findings, recently published in the journal Additive Manufacturing, focus on Ti-6Al-4V, a widely used titanium alloy known for its high strength and low weight. The team leveraged AI-driven models to map out previously unexplored manufacturing conditions for laser powder bed fusion, a method of 3D-printing metal. The results challenge long-held assumptions about process limits, revealing a broader processing window for producing dense, high-quality titanium with customizable mechanical properties.

The discovery provides a new way to think about materials processing, said co-author Brendan Croom.

“For years, we assumed that certain processing parameters were ‘off-limits’ for all materials because they would result in poor-quality end product,” said Croom, a senior materials scientist at APL. “But by using AI to explore the full range of possibilities, we discovered new processing regions that allow for faster printing while maintaining — or even improving — material strength and ductility, the ability to stretch or deform without breaking. Now, engineers can select the optimal processing settings based on their specific needs.”

These findings hold promise for industries that rely on high-performance titanium parts. The ability to manufacture stronger, lighter components at greater speeds could improve efficiency in shipbuilding, aviation and medical devices. It also contributes to a broader effort to advance additive manufacturing for aerospace and defense.

Researchers at the Whiting School of Engineering, including Somnath Ghosh, are integrating AI-driven simulations to better predict how additively manufactured materials will perform in extreme environments. Ghosh co-leads one of two NASA Space Technology Research Institutes (STRIs), a collaboration between Johns Hopkins and Carnegie Mellon focused on developing advanced computational models to accelerate material qualification and certification. The goal is to reduce the time required to design, test and validate new materials for space applications — a challenge that closely aligns with APL’s efforts to refine and accelerate titanium manufacturing.