Results and Expectations

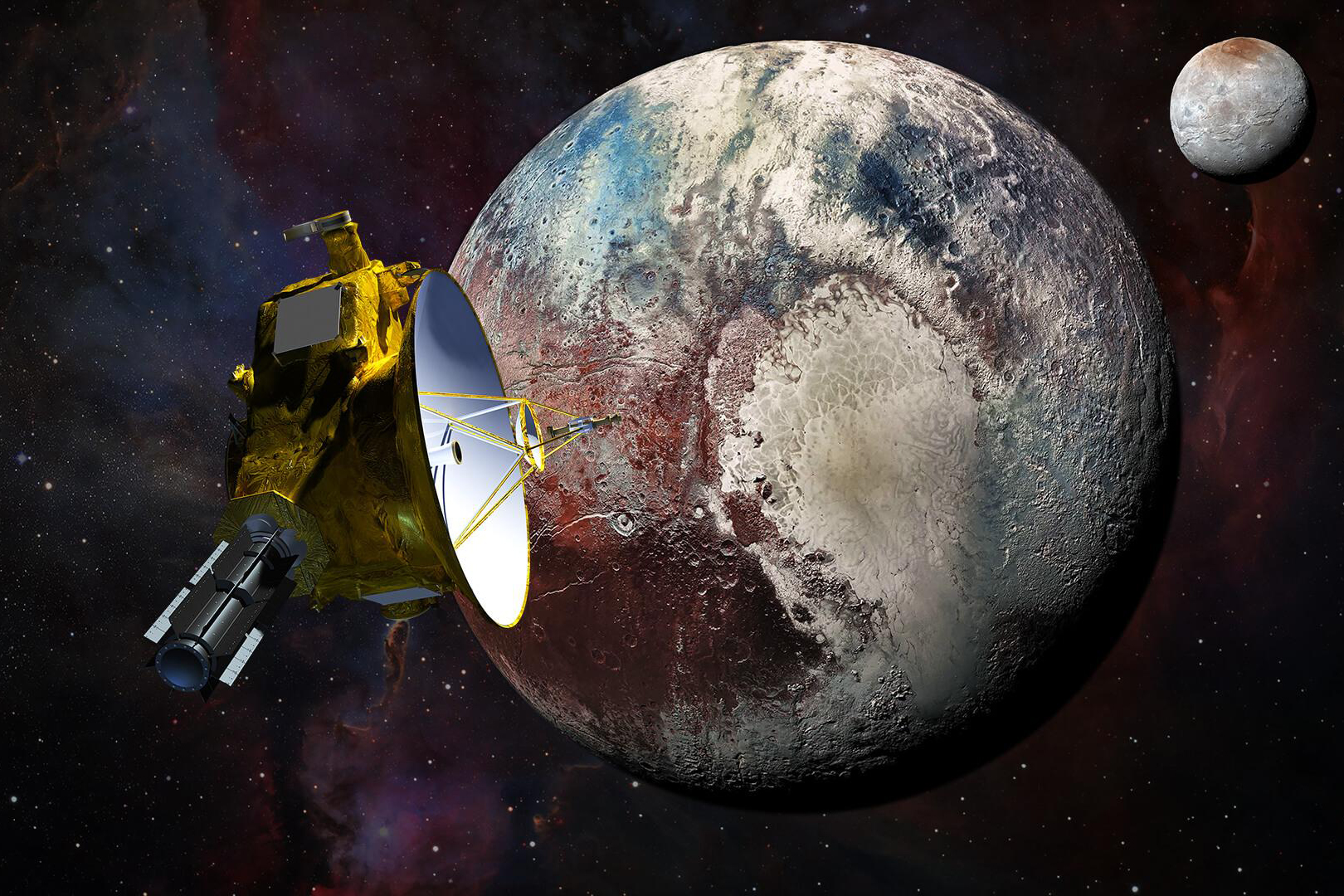

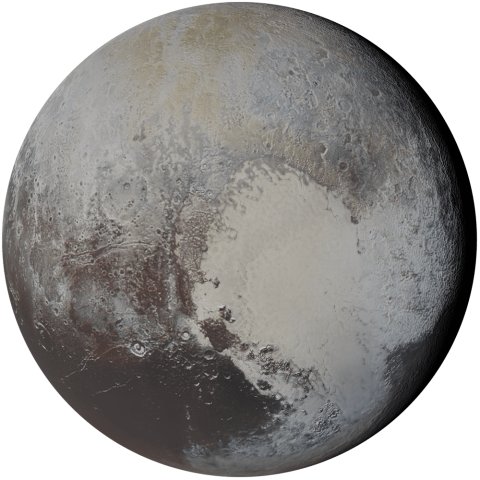

The flyby of Pluto and its moons on July 14, 2015, was a resounding success. New Horizons sent home data that resulted in profound new insights about Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, most surprisingly that Pluto is still geologically active after 4.5 billion years and likely has a liquid water ocean under its icy crust.

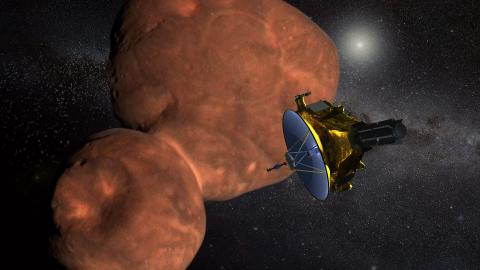

New Horizons broke its own record of farthest planetary exploration with its close flyby of a Kuiper Belt object called 2014 MU69—officially named Arrokoth (Powhatan and Algonquian for “sky”)—on Jan. 1, 2019. Geologic evidence on Arrokoth showed that its two defining lobes merged at the dawn of the solar system in a gentle, mile-per-hour collision or “docking.”

The Kuiper Belt is a scientifically rich frontier. Its exploration has important implications for better understanding comets, small planets (some of which have or once had underground oceans), the solar system as a whole, the solar nebula, and disks around other stars. It’s a natural laboratory for studying well-preserved, primitive material from the ancient era of planet formation.

The New Horizons Kuiper Belt Extended Mission, however, is much more than the close flyby of Arrokoth. The continuing mission also takes advantage of the unique capabilities of New Horizons as an observation platform in the Kuiper Belt to study dozens of other Kuiper Belt objects in multiple ways that can’t be done from Earth.

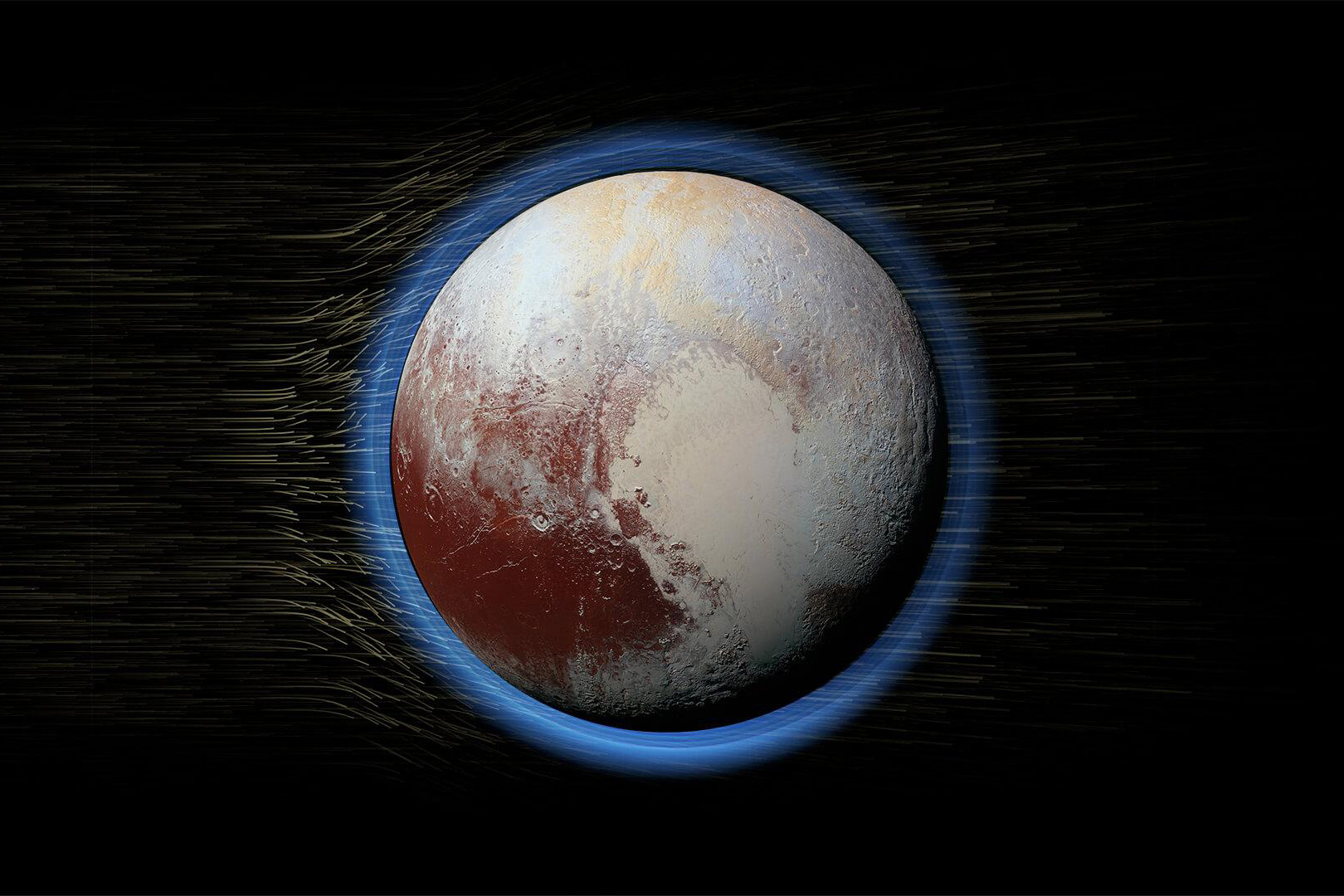

Hurtling toward the doorstep of interstellar space, New Horizons is also making groundbreaking measurements of dust and the heliospheric plasma environment far from the Sun.