Feature Story

Paving the Way

Jamie Porter, Mareena Robinson Snowden and Ciara Sivels were each the first black woman to earn a Doctor of Philosophy in nuclear engineering from their respective colleges. Now, they work in three different sectors at APL, dedicating their time and their brains to important challenges facing the nation — with an eye toward furthering a sea change in their wake.

The corner conference room in Building 26 on the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory’s Laurel, Maryland, campus is small and windowed. On most days, it is indistinguishable from the many quiet work spaces that surround it. But on a gray afternoon in mid-February, the voices, laughter and energy bounding from its occupants differentiate it from the rest.

As Jamie Porter, Mareena Robinson Snowden and Ciara Sivels gather around the small table inside, the feeling of stumbling onto a gathering of old friends is difficult to shake. Their bonds, though, are forged less through time than their shared experience of being “the first.”

Each one — Porter, APL’s radiation effects lead for NASA’s Europa Clipper mission; Snowden, a senior engineer in the National Security Analysis Department; and Sivels, a nuclear engineer in the Air and Missile Defense Sector — was the first black woman to earn a Doctor of Philosophy in nuclear engineering from their respective colleges.

We have to create space for ourselves and each other. I just didn’t want to be a data point in somebody else’s story, giving them license to back out. I wanted to be someone like the women who are data points for me — who I can look at and say, ‘She fought. She won. I can do it.’

It’s that distinction that brought them together in this particular conference room on this particular afternoon, because theirs is an exclusive group.

How exclusive? When the question is posed, Porter (University of Tennessee, 2012), Snowden (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2018) and Sivels (University of Michigan, 2018) begin counting on their fingers and naming the other African American women they know with nuclear engineering doctorate degrees…nationwide.

“There are a lot of fields where there hasn’t even been one,” Snowden says, explaining that, as a result, these three women and their nuclear-engineering-Ph.D.’d counterparts are grouped under the umbrella of African American Women in Physics, a list that, she notes, recently registered its 100th entry.

Porter, Snowden and Sivels work in three different sectors at APL, dedicating their time and their brains to important challenges facing the nation. Here, they have created a community.

“We have to create space for ourselves and each other,” Snowden says. “I just didn’t want to be a data point in somebody else’s story, giving them license to back out. I wanted to be someone like the women who are data points for me — who I can look at and say, ‘She fought. She won. I can do it.’”

Path to the Ph.D.

“I used to hate physics,” Porter says with a laugh. “Lord, I don’t know how, but now I live in this world.”

Referring to herself as the “elder” of the group, Porter arrived in APL’s Space Exploration Sector in 2015. She focuses on radiation hardness assurance for all electric, electrical and electrochemical parts of missions, specifically NASA’s planned Europa Clipper mission to Jupiter’s icy moon. She also manages the sector’s Radiation Analysis and Test section.

Three years before she arrived at APL, Porter was the first black woman to earn a Ph.D. in nuclear engineering from the University of Tennessee. It’s likely, Porter said, that she was just the second black woman in the country to do so, after J’Tia Hart, who received hers from the University of Illinois and subsequently appeared on Season 28 of the CBS show “Survivor.”

Photo credit: Jamie Porter

After completing her undergraduate studies, Porter said her goal was to get a master’s. No, thank you, her professor and graduate advisor Lawrence Townsend told her. A Ph.D. was what she needed. Porter credited Townsend for pushing her — from undergraduate classes through her doctorate, and even a postdoctoral fellowship.

“He is an old Navy guy,” Porter said, describing her relationship with Townsend as that of a “surrogate father.” “He’s white, but he pushed for minority students. He always had all the students other people would brush off. He was adamant that I needed to do the Ph.D.

“He told me, ‘You need to do this for yourself, and you need to do this for other people.’”

It wasn’t until Porter was nearing her graduation that Tennessee discovered she’d be their first. They didn’t publicize it at the time — a decision reached through a conversation with Porter, where the school admitted embarrassment that it took until 2012 to reach the milestone. They later acknowledged regret at not celebrating it more publicly.

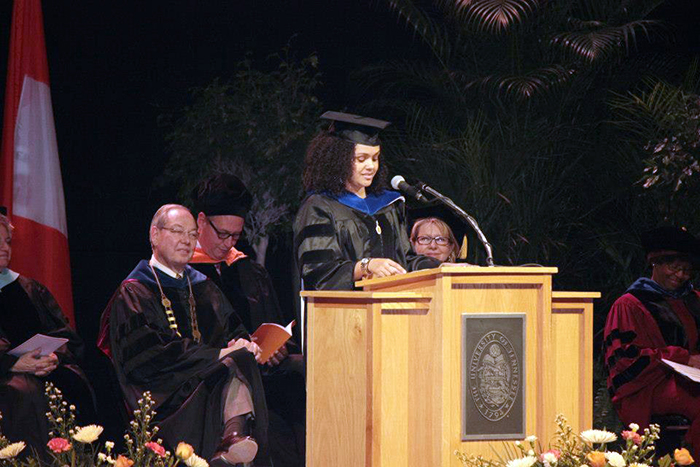

“I actually got to be the speaker at the hooding ceremony the year after I graduated, and it resonated with a lot of people,” Porter said. “When you go through school, to an extent you feel like ‘I’m just doing what I’m supposed to do,’ but the representation alone resonated.”

For Snowden, that wasn’t necessarily the case. When she became the first black woman to earn a nuclear engineering Ph.D. from MIT in 2018, it was well publicized, particularly after her own Instagram post from graduation day went viral. That doesn’t mean her path to that moment was smooth. In retrospect, it wasn’t even a path she necessarily chose.

“People ask me, ‘How did you pick nuclear engineering?’ and I’m like, nuclear engineering picked me. You get a ticket, you get on the train,” she said.

Photo credit: Mareena Robinson Snowden

Snowden credited her father, Bill Robinson (an attorney), with guiding her into studying physics as an undergraduate at Florida A&M University, a historically black college in Tallahassee. It was a visit with a friend of a friend who worked at the school that started her trajectory.

“We went on a visit to the physics department and these people treated me like I was a football recruit,” Snowden says, bursting into laughter after delivering the line. “It’s so rare for somebody to come off the street asking about a physics program. They were like ‘Listen, Mareena, we want you to come here.’ They didn’t know anything about my GPA, nothing.”

The mantra of FAMU, though, is that they don’t expect you to be the best student on the way in, but you will be the best and most competitive student on the way out. That, Snowden said, was absolutely her experience. “I was in office hours every semester. I often thought ‘I don’t know if this is for me,’” she said.

It was acceptance into a summer research program at MIT after her freshman year that set Snowden on a firmer course. “It was the only application I sent out because I just knew I was going to be at FAM’ doing research in the lab like normal,” she said. “But they messed around and accepted me. And we celebrated like I got into the Ph.D. program.”

A few years later, she did that, too.

Snowden, whose work at APL leverages her technical training in nuclear engineering on current and future national security challenges, applied to eight graduate schools. She got into one.

That’s where she met Sivels.

Sivels and Snowden first connected when the former was an undergraduate MIT student in nuclear engineering and the latter was working toward her Ph.D. That fact alone would knock a 16-year-old Sivels over with a feather.

“I wanted to be a chef,” she said. “That was my plan.”

In Sivels’ case, a chemistry teacher pushed her to explore her options — urging her to take his class (Advanced Placement Chemistry) as a senior, recommending she look into chemical engineering schools, and turning her down time after time as she suggested potential colleges that might be a good fit.

“He kept saying ‘This isn’t good enough, this isn’t good enough,’” Sivels recalled. “He would just say ‘Try something else.’”

In an effort to boost her credentials for engineering school, Sivels enrolled in a local community college physics class that covered the history of the discipline. Fascinated by antimatter, she read about work at the California Institute of Technology. The Virginia native showed that school to her mom, who nixed the idea. But as she researched Caltech further, their rival, MIT, began popping up.

“I didn’t know what MIT was, the prestige associated with it, anything,” said Sivels, whose work at APL focuses on how radiation interacts with and changes the properties of various types of materials. “It just came up in the sentence with Caltech, so I took it back to my teacher, Robert Harrell, and he was like ‘Oh yeah, that’s the kind of school you need to be applying to.’”

Photo credit: Ciara Sivels

Even after she was accepted, Sivels was certain she’d be attending Virginia Commonwealth University. It was a campus visit to MIT — coupled with the release of the movie “21” — that helped convince her of the school’s esteemed reputation. “Before that, the only people who were making a big deal about my acceptance were the kids in my class who didn’t get in,” Sivels said. “Because most people in my circle, we just didn’t know.”

It was hard.

“I got there, and I struggled,” Sivels said, noting, among other setbacks, she failed a class and shed many a tear. She got through it, and knew she wanted to further her impact in the field. That’s when her advisors suggested moving on to Michigan for her graduate education.

And it wasn’t until she went searching for a mentor there — preferably another black woman who’d gone through the program — that Michigan noted she’d be the first. “Nobody knew until I asked the question,” she said, which she did on the advice of Snowden, who’d done the same at MIT.

The Challenges of Being the First

In many ways, these women know they are the exception, not the rule.

That they were able to navigate turbulent waters and persevere through biases and other challenges on their way to sitting around that conference room table on that February afternoon is a testament to their intelligence and resilience.

It doesn’t mean, however, that just because they did it, black women trying to get nuclear engineering Ph.D.s are suddenly no longer the exception.

“I come from an HBCU [Historically Black Colleges and Universities], and so much of that culture and legacy is about that question of responsibility,” Snowden said. “FAMU was intentional about teaching us the context — about what it meant to be black in America and in professional spaces. I went into my Ph.D. process with that context, so when I came up against a challenge, or a person coming at me sideways, I could leverage that context to help me interpret the situation.”

My parents didn’t want to jade me, but they knew I was smart and they knew it was coming. They sat me down and they said it straight out: You’re about to go somewhere new. You’re going to be the only one. Be prepared. They’re going to test you.

“Both of my parents went to HBCUs, so I had that training, too,” Sivels added. “My parents didn’t want to jade me, but they knew I was smart and they knew it was coming. They sat me down and they said it straight out: You’re about to go somewhere new. You’re going to be the only one. Be prepared. They’re going to test you. When I used to cry to them at MIT, my parents were like ‘You’ll get over it. Welcome to the world — something is finally hard for you.’”

“I feel like I’ve always had to recognize that I was going to get treated differently and that I have to be better to do the same job,” said Porter, who grew up in Tennessee with a white mother and a black father. “There are moments when I am like gosh, I do feel the pressure, because I have to deal with comments or expectations that my counterpart does not. Sometimes I will send out an e-mail that says ‘This is a learning moment, please do not do this [thing you may not think is offensive, but is offensive],’ and I’ll put it out there because I feel like…”

As Porter trails off, Sivels jumps in. “If you don’t, who will?”

“That’s exactly right,” Porter said. “But it’s hard. You have to pick and choose your battles. You have to think ‘How is this going to affect me if I react right now?’”

Snowden has a theory about that thought process — one most professional women and minorities are likely familiar with. “I read a paper once that talked about that,” she said. “They called it the tax. It’s the tax you have to pay of being ‘one of only’ of an identity. That extra calculation you have to do in your mind of ‘How am I going to be perceived in this environment? How do I respond to this stimulus?’ That’s a tax your counterparts from majority populations don’t have to pay.”

And that, the women noted emphatically, doesn’t even include bouts of impostor syndrome that are often lurking just around the corner even as they continue their ascents.

For Sivels, that reared its head predominantly in her conditional admittance to the Ph.D. program at Michigan — which sent her on a path for a master’s first. “They weren’t rejecting me, but it was really hard,” Sivels said. “I was like ‘Dang, I just got this degree from MIT and they’re telling me I’m not good enough? I know these classes aren’t going to be harder than MIT’s, but…am I supposed to be here?’”

Eyes on the Future

Porter, Snowden and Sivels have an ease about them as they discuss their experiences and delve into important, personal topics. To listen to them, though, you’d think their trailblazing happened with a shrug of the shoulders — they just put their heads down and did what they thought they were supposed to do. The truth is, it wasn’t nearly so simple.

They also know the rewards of their perseverance come with a duty to future generations.

People naturally want to help those who remind them of themselves. If I don’t do it, nobody else is going to look at black girls after me and say ’Oh, she reminds me of myself.

“I definitely feel a responsibility,” Porter said. “I am the lead radiation engineer for a billion-dollar flagship NASA mission, and when I do reviews most often I am the only black person in the room. So, I try really hard to bring people with me. People naturally want to help those who remind them of themselves. If I don’t do it, nobody else is going to look at black girls after me and say ‘Oh, she reminds me of myself.’”

They make an effort to mentor those behind them — to be a part of the community that each of them relied on so heavily as students. They work on committees, and in outreach programs, like the IF/THEN Ambassador program, of which Sivels is a part.

And they tell their stories. They talk about their journeys so that their shared experiences as “the first” are ultimately just a way to pave the road for those behind them.

“People don’t know these stories,” Sivels said. “If you don’t tell them, they’ll never know.”

“I look at the diversity and inclusion conversation as two sides to one coin,” Snowden said. “You have the recruitment piece, and the second, less-talked-about part, is the retention piece. Once they’ve gotten into these programs, and they’ve gotten their Ph.D.s and they’re STEM professionals, how do we get them to and through mid-career, promoted up to senior levels, given power so they can hire, and all of those types of things that will make an impact?

“Now, I think the mission is to preserve the recruitment momentum but create a new body of momentum on the retention piece, but it’s the harder challenge to me.”

Snowden understands that hers isn’t an easy question to answer. It takes organizations engaging in self-reflection, tracking the numbers, and setting concrete, transparent goals toward which to strive.

In a way, what Porter, Snowden and Sivels would like is for their accomplishments as “the firsts” to fade. For them to be the firsts of many — and for that to extend through to professional life.

“I love outreach,” Porter said. “It’s telling your story. It’s letting a little girl see what’s possible. [Snowden and Sivels] saw each other [at MIT], but they didn’t really see it was possible until it happened. I didn’t see anybody and it was just like ‘Well, this is happening.’

“But it all goes back to that responsibility and the fact that now we have that responsibility to put ourselves out there — so other girls can see it’s possible.”