Press Release

New Research Offers Explanation for Titan Sand Dune Mystery

Mon, 12/08/2014 - 10:35

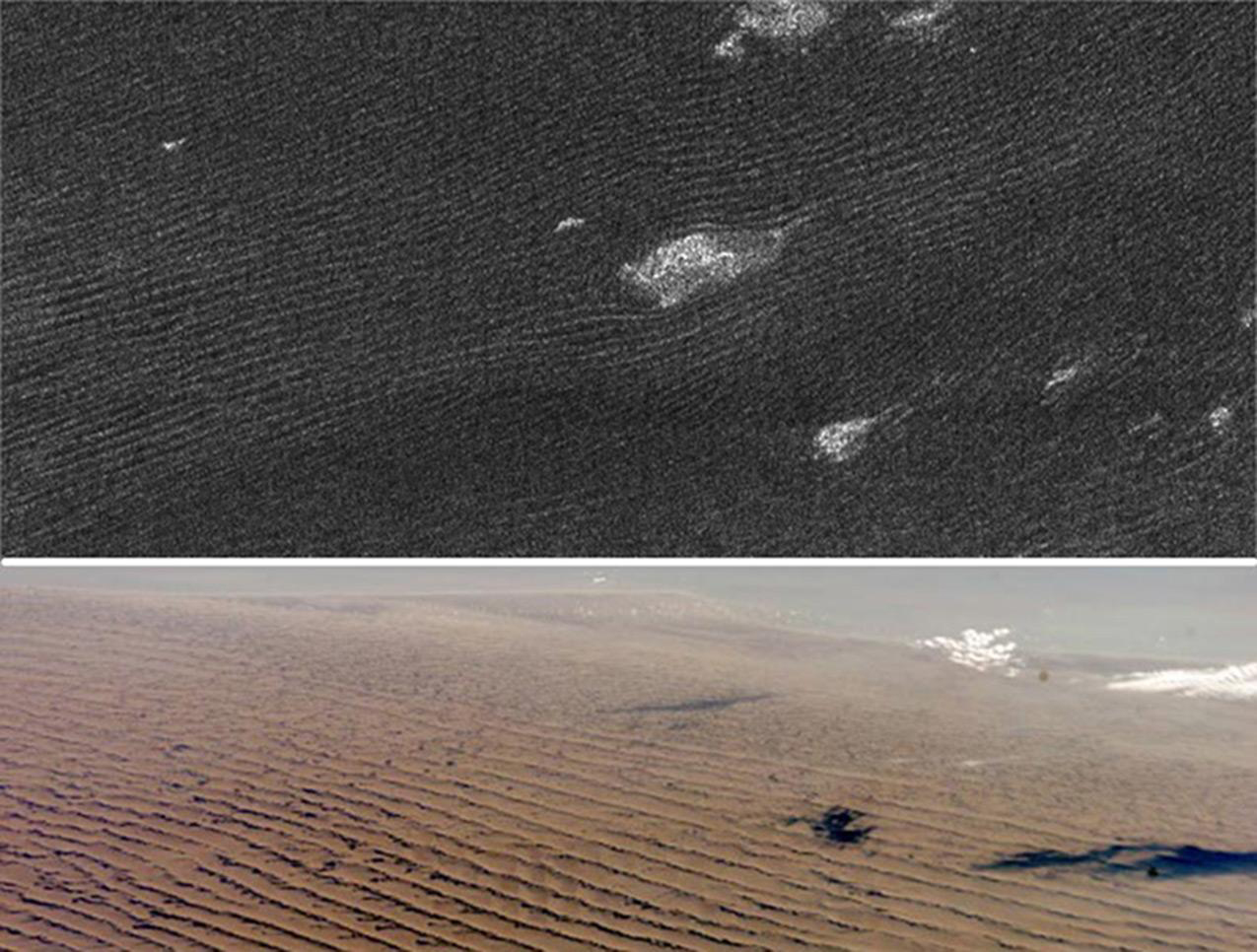

Titan, Saturn’s largest moon, is a peculiar place. Unlike any other moon in our solar system, it has a dense atmosphere. Thanks to imagery from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, we also know that Titan has rivers and lakes made of ethane and methane, as well as windswept sand dunes that are dozens of yards high, more than a mile wide and hundreds of miles long. What scientists have not known is how they were created, because current data suggested that Titan’s winds were not strong enough to form the dunes spotted by Cassini.

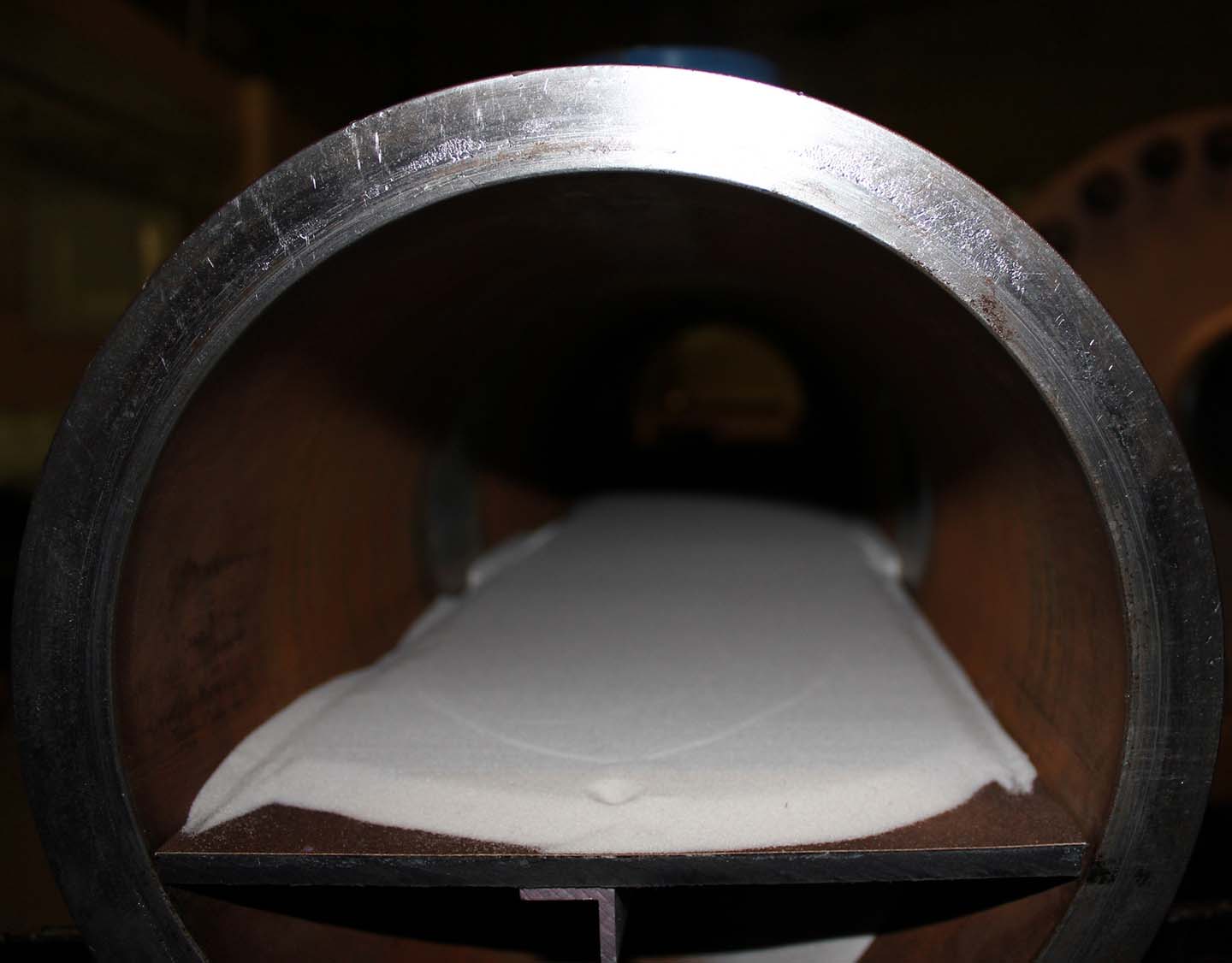

A team of researchers has now shown that winds on Titan must blow 50 percent faster than previously thought in order to move that sand. This discovery may explain how the dunes were formed and could inform observations made on other planetary bodies. The findings are published in the current edition of the journal Nature.

Scientists were amazed by the first radar images of Titan returned by the Cassini spacecraft a decade ago. The images showed never-before-seen dunes created by particles not previously known to have existed.

“It was surprising that Titan had particles the size of grains of sand — we still don’t understand their source — and that it had winds strong enough to move them,” said Devon Burr, an associate professor in the Earth and Planetary Sciences Department at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and lead author of the paper. “Before seeing the images, we thought that the winds were likely too light to accomplish this movement.”

The biggest mystery, however, was the shape of the dunes. The Cassini data showed that the predominant winds that shaped the dunes blew from east to west. However, the streamlined appearance of the dunes around features like mountains and craters indicated they were created by winds moving in exactly the opposite direction.

“Until now, there’s been a big mystery as to why most winds on Titan blow from the east, yet the dunes appear to form from westerly winds,” said Nathan Bridges, planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, and a coauthor of the paper.