Press Release

What ‘Belted’ Asteroid Vesta?

Thu, 11/06/2014 - 11:51

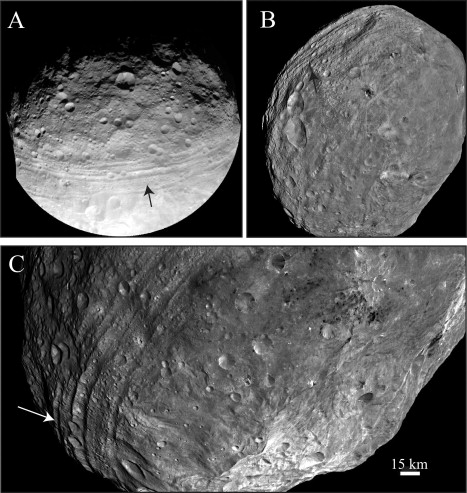

When NASA’s Dawn spacecraft visited the asteroid Vesta in 2011, it showed that deep grooves that circle the asteroid’s equator like a cosmic belt were probably caused by a massive impact on Vesta’s south pole. Using a super-high-speed cannon at NASA’s Ames Research Center, Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab and Brown University researchers recently shed new light on the violent chain of events deep in Vesta’s interior that formed those surface grooves, some of which are wider than the Grand Canyon.

“Vesta got hammered,” said Peter Schultz, professor of Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences at Brown. “The whole interior was reverberating, and what we see on the surface is the manifestation of what happened in the interior.”

The research, led by Angela Stickle, a former graduate student at Brown and now a researcher at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, will appear in the February issue of the journal Icarus and is now available online.

The work suggests that the Rheasilvia basin on Vesta’s south pole was created by an impactor that came in at an angle, rather than straight on. But that glancing blow still did an almost unimaginable amount of damage. The study shows that just seconds after the collision, rocks deep inside the asteroid began to crack and crumble under the stress. Within two minutes major faults reached near the surface, forming deep the canyons seen today near Vesta’s equator, far from the impact point.

“As soon as Pete and I saw the images coming down from the Dawn mission at Vesta, we were really excited,” Stickle said. “The large fractures looked just like things we saw in our experiments. So we decided to look into them in more detail, and run the models, and we found really interesting relationships.”

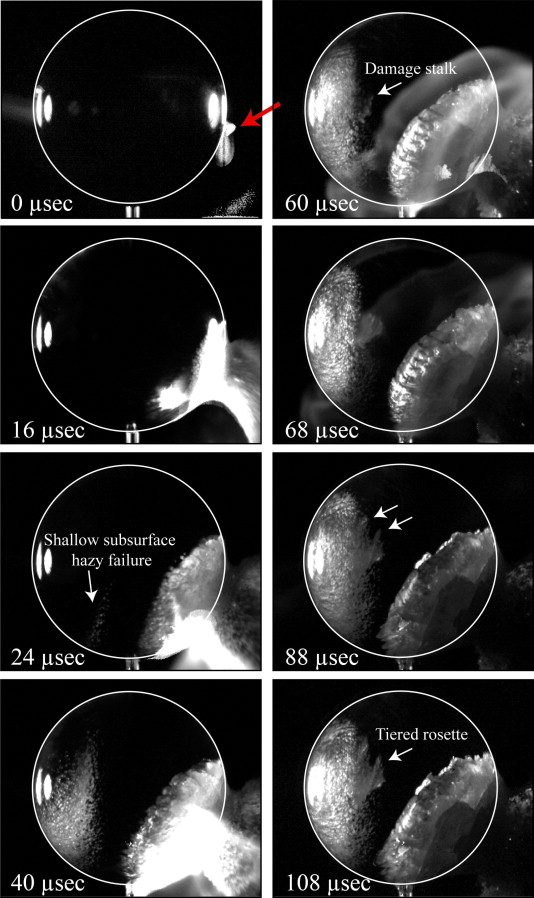

For the study, the researchers used the Ames Vertical Gun Range, a cannon with a 14-foot barrel used to simulate collisions on celestial bodies. The gun uses compressed hydrogen gas and gunpowder to launch projectiles at blinding speed, up to 16,000 miles per hour. For this latest research, Stickle and colleagues launched small projectiles at softball-sized spheres made of an acrylic material called PMMA. When struck, the normally clear material turns opaque at points of high stress. By watching the impact with high-speed cameras that take a million shots per second, the researchers can see how these stresses propagate through the material.

The experiments showed that damage from the impact starts where one would expect: at the impact point. But shortly after, failure patterns begin to form inside the sphere, opposite the point of impact. Those failures grow inward toward the sphere’s center and then propagate outward toward the edges of the sphere like a blooming flower.